Hashtags

#SanMarcosEarthquake #MexicoEarthquake2026 #SeismicRisk #NaturalDisaster #Aftershocks #EarthquakePreparedness #Guerrero #PlateTectonics #DisasterResponse

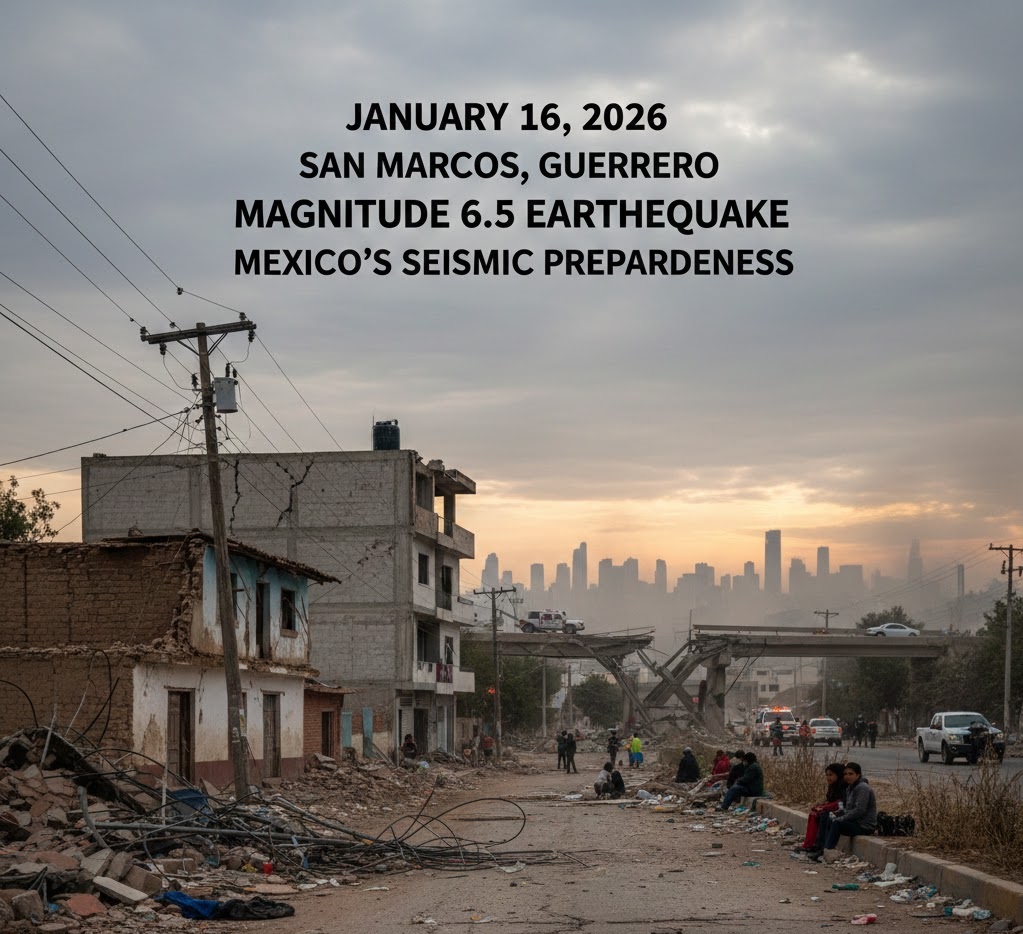

The January 2026 San Marcos Earthquake: A Comprehensive Analysis of Mexico’s Latest Seismic Crisis

The ground beneath San Marcos, Guerrero convulsed violently for 33 seconds on January 16, 2026, unleashing a moment magnitude 6.5 earthquake that would test Mexico’s seismic preparedness systems and expose vulnerabilities in infrastructure spanning multiple states. Those half-minute tremors represented the sudden release of tectonic forces that had been accumulating for years along one of the world’s most geologically volatile plate boundaries. What followed wasn’t just the immediate devastation—it was a cascading series of aftershocks, structural failures, and cascading utility disruptions that revealed how even a prepared nation struggles when the earth beneath its cities decides to shift.

This wasn’t Mexico’s first major earthquake, nor will it be the last. The country sits atop a geological pressure cooker where three massive tectonic plates grind against each other in slow motion, storing energy that periodically releases in catastrophic bursts. Understanding what happened in January 2026 requires examining not just the event itself but the deep geological processes that made it inevitable, the infrastructure vulnerabilities it exposed, and the thousands of aftershocks that continued terrorizing survivors long after the initial shaking stopped.

The human cost emerged quickly—fatalities during panicked evacuations, injuries from collapsing structures, and the psychological trauma of feeling solid ground betray its promise of stability. But the full impact extends far beyond immediate casualties to include 5,380 damaged homes, crippled transportation networks, and utility systems pushed to failure across multiple states. This analysis examines how a 33-second seismic event created consequences that will reverberate through affected communities for years.

Geological Origins: The Subduction Zone Mechanism

Mexico’s position at the convergence of three major tectonic plates—the North American, Pacific, and Cocos plates—makes seismic activity an inescapable reality rather than a rare occurrence. These aren’t static boundaries but dynamic zones where massive chunks of the Earth’s crust interact through processes operating on timescales spanning millions of years. The specific mechanism that generated the January 2026 earthquake involves the Cocos plate, an oceanic tectonic plate that’s being forced beneath the continental North American plate in a process geologists term subduction.

This subduction occurs along the Middle America Trench, a seafloor depression marking where one plate dives beneath another. The Cocos plate, composed of denser oceanic crust, slides underneath the lighter continental crust of the North American plate at rates measuring several centimeters annually. This sounds gradual, but the immense forces involved create friction at the plate interface that locks the boundary in place. Stress accumulates as the deeper portions of the subducting plate continue moving while the shallower sections remain stuck.

Eventually, the accumulated elastic strain exceeds the frictional forces holding the plates together, and the locked section ruptures suddenly. The overlying plate snaps back toward its undeformed position, displacing millions of tons of rock in seconds. This sudden motion propagates as seismic waves radiating outward from the rupture zone, carrying energy that shakes the surface sometimes hundreds of kilometers from the actual fault movement.

The January 2026 earthquake released strain that had been building since the last major rupture in this specific segment of the subduction zone. Geological surveys had identified this region as a seismic gap—an area along an active fault that hasn’t experienced recent earthquakes despite adjacent segments rupturing. These gaps represent zones of concern because they indicate sections where stress continues accumulating without release, making large earthquakes not just possible but probable on timescales relevant to infrastructure planning and building codes.

The 33-second duration of strong shaking reflects the time required for the rupture to propagate along the fault surface and for seismic waves to pass through the affected region. Shorter ruptures produce brief but potentially intense shaking, while longer ruptures sustain shaking that gives structures more time to accumulate damage through repeated stress cycles. The specific fault geometry, rupture velocity, and distance from population centers all influence how that energy translates into surface destruction.

Shaking Intensity and Regional Spread

The maximum recorded intensity reached Modified Mercalli Intensity VI (Strong), a level where damage becomes significant for poorly constructed buildings while engineered structures typically survive with varying degrees of damage. MMI VI shaking causes furniture to move, plaster to crack, and poorly built structures to experience partial collapse. People have difficulty standing, and the sensation is universally frightening for those experiencing it. This intensity represents the threshold where earthquakes transition from inconvenient natural phenomena to genuine disasters requiring emergency response.

The shaking extended far beyond the immediate epicentral region, with felt reports documented across Oaxaca, Veracruz, Puebla, Jalisco, and Michoacán. This geographic spread reflects how seismic waves propagate through the Earth’s crust, with different wave types traveling at different velocities and affecting structures in distinct ways. The primary waves arrive first, causing initial jolts that alert people something is happening. Secondary waves follow, producing the rolling motion that causes the most structural damage. Surface waves, traveling along the Earth’s exterior, can sustain shaking for the longest duration despite carrying less energy than body waves.

Mexico City, despite being over 300 kilometers from the epicenter, experienced notable shaking due to site amplification effects. The city sits atop the drained lakebed of Lake Texcoco, where soft sediments amplify seismic waves like a bowl of gelatin responds to table bumps. This geological quirk has repeatedly turned distant earthquakes into local catastrophes, as seen in the devastating 1985 earthquake that killed thousands despite originating far from the capital.

Perhaps most concerning for affected populations was the aftershock sequence—2,144 recorded events within just the first few days following the main shock. This relentless continuation of seismic activity prevents psychological recovery, damages structures already weakened by the initial earthquake, and complicates rescue operations as workers must repeatedly evacuate buildings when aftershocks strike. Each aftershock triggers the same physiological fear response as the original earthquake, creating cumulative trauma that persists long after shaking stops.

The aftershock statistics follow patterns that seismologists describe with empirical laws like Omori’s Law, which predicts aftershock frequency decaying with time following the main event. However, these predictions offer cold comfort to residents sleeping in cars or refusing to enter buildings because they cannot know which aftershock might be “the big one” that brings down structures the main shock merely weakened.

Detailed Impact and Damage Assessment

Guerrero State bore the brunt of destruction, with damage assessments documenting 5,380 homes affected across 23 municipalities. This figure represents only formally surveyed damage—the actual number of affected structures likely exceeds official counts given the challenges of conducting comprehensive assessments across rural and mountainous terrain. The damaged homes range from minor cosmetic cracking to complete collapse, with the severity depending on construction quality, building age, and proximity to areas experiencing strongest shaking.

Traditional adobe and unreinforced masonry construction, common in rural communities throughout Guerrero, performs particularly poorly during earthquakes. These materials lack the tensile strength and ductility that allow modern engineered structures to flex during shaking without catastrophic failure. When walls crack, they lose load-bearing capacity, leading to progressive collapse that can occur during the initial shock or during subsequent aftershocks that exploit existing damage.

Transportation infrastructure suffered disruptions that cascaded beyond immediate damage zones. Acapulco International Airport reported structural damage requiring inspections before resuming full operations, stranding travelers and delaying cargo shipments. Mexico City International Airport experienced similar precautionary shutdowns, inspecting runways, terminals, and air traffic control facilities for damage that could compromise safety. These closures ripple through global transportation networks, affecting not just local travelers but international connections that depend on these facilities as regional hubs.

Mexico City experienced fatalities not from building collapse but from evacuation panic. When earthquake alerts sounded and shaking began, crowds rushed from buildings into streets, creating stampede conditions where people were trampled or suffered falls on stairs and through doorways. This grim reality highlights a challenging aspect of earthquake preparedness—sometimes the evacuation causes more harm than sheltering in place within properly engineered structures would have. However, making real-time decisions about whether specific shaking justifies evacuation remains nearly impossible for ordinary citizens experiencing terrifying ground motion.

Power outages affected extensive areas as electrical distribution systems failed. Substations experienced equipment damage from shaking, while transmission lines suffered physical damage or protective systems triggered shutdowns to prevent further damage or fire risk. One electrical substation fire illustrated the cascading hazards earthquakes create—the initial shaking damaged equipment, which then failed electrically, creating arcing that ignited flammable materials or insulation. These fires threaten to spread while emergency services are overwhelmed responding to earthquake damage, potentially creating compound disasters.

Gas leaks represented another critical hazard as underground pipelines fractured from ground shaking or differential settlement. Natural gas is both explosive and toxic, requiring immediate response to prevent fires or asphyxiation. Utility companies must inspect entire distribution networks before restoring service, a time-consuming process when damage is widespread. Landslides triggered by shaking buried roads, damaged structures, and altered drainage patterns in ways that create ongoing hazards even after seismic activity subsides.

Continued Risk: The January 16 Strongest Aftershock

The mb 4.9 aftershock that struck shortly after the main event deserves specific attention because it illustrates how aftershock sequences pose distinct challenges beyond simply being smaller earthquakes. This event, while significantly lower magnitude than the main shock, occurred when structures were already damaged and populations were psychologically vulnerable. Buildings that survived the initial earthquake with minor damage experienced additional stress cycles that propagated existing cracks and potentially triggered collapse in marginally stable structures.

San Marcos homes that might have been repairable after the main shock suffered additional damage that pushed them beyond economic repair. This isn’t just about cumulative physical damage—it’s about how repeated seismic events affect decision-making by residents, engineers, and government officials. Do you repair a home after the first earthquake if aftershocks might destroy it before repairs complete? Do you allow occupancy of damaged buildings when aftershocks remain likely? These questions lack clear answers but demand immediate decisions affecting thousands of families.

The magnitude 4.9 event also tested emergency response systems already stretched by the main earthquake. First responders, already working to capacity on search and rescue operations and damage assessment, had to pause operations and take cover themselves. Hospitals treating injured patients had to implement earthquake protocols while simultaneously caring for existing patients. The compounding stress on both infrastructure and human systems highlights why aftershock sequences often determine whether communities recover quickly or descend into prolonged crisis.

Historical Context and Future Preparedness

The January 2026 earthquake joins a long history of significant seismic events affecting Guerrero and surrounding regions. The 1985 Mexico City earthquake, despite originating hundreds of kilometers away in a similar subduction zone rupture, killed over 10,000 people and fundamentally changed how Mexico approaches seismic risk. That catastrophe prompted massive investments in building codes, seismic monitoring networks, and public earthquake preparedness education that undoubtedly reduced casualties in 2026.

The Advanced National Seismic System (ANSS) and Mexico’s Seismic Alert System demonstrated their value by providing seconds to tens of seconds of warning before strong shaking arrived at distant locations. This warning time, though brief, allows automated systems to shut down sensitive equipment, halt trains, and trigger building safety protocols. People receive alerts on smartphones and through public address systems, enabling them to take cover before the worst shaking begins.

However, comparing 2026 to historical events reveals both progress and persistent vulnerabilities. Modern engineered structures in major cities largely performed as designed, flexing during shaking without collapse. Rural construction using traditional methods and materials continues experiencing disproportionate damage, highlighting the challenge of extending seismic safety to economically disadvantaged communities where expensive modern construction remains unaffordable.

Future preparedness must address not just building codes and monitoring systems but the socioeconomic factors that leave certain populations vulnerable regardless of technical capabilities. Retrofitting existing structures, enforcing building codes in informal settlements, and ensuring emergency response resources reach remote communities require sustained political will and resource allocation that often evaporates between disasters.

The geological reality remains unchanged—the Cocos plate continues subducting beneath the North American plate, accumulating strain that will inevitably release in future earthquakes. Seismic gaps along the Middle America Trench represent zones where major earthquakes are overdue based on historical rupture patterns. The question isn’t whether another major earthquake will strike Mexico, but when, and whether the lessons from January 2026 will translate into actions that reduce casualties when it does.

The 33 seconds of shaking that began on January 16, 2026, will fade from memory for those unaffected, but for thousands of families in Guerrero and neighboring states, that half-minute marked a dividing line between before and after. The damaged homes, disrupted lives, and psychological scars represent the human cost of living on a geologically active planet. Understanding these events scientifically doesn’t diminish their impact but hopefully informs the preparations that might reduce suffering when the earth inevitably shakes again.